Frostpunk 2 was an ambitious gambit. With survival achieved, and the introduction’s excellently sinister advisor whispering evil Tory ideas, the whole city you built in Frostpunk is now just the headquarters for a sprawling expansion effort, and your rule is no longer absolute. Rather than retread the same “prepare for ultra-Winter” ground, your biggest obstacle will likely be your own people, now formed into shifting political parties, and looking outward with colonial eyes. The result is a complicated, laborious survival citybuilder that’s two parts compelling, and one part frustrating for the wrong reasons.

It’s more political, in a word. Your predecessor might have been a monster but it was undeniable that without some ruthless leadership, everyone would die horribly. Here that’s less certain, so you’re dependent on overtly bargaining with the nascent social groups who vote directly on every law, and even propose their own. Every law, every building, every research project pulls the ‘zeitgeist’ towards one of six values like Adaptability, Tradition, and Equality in addition to their practical effects. Factions favour different values, and the radical ones are also differentiated by their mutually exclusive plans for all the resources you’ll be hoovering from the world.

There are simultaneously too many ways you and the factions can interact to list, and too few to do much about the massive problems they are very obviously going to cause in the long run. The early chapters are a breeze politically, as you promise everyone easy things you already wanted in exchange for legislation that sets up the society you want. But by midway through my game, most factions wanted things that would only screw everything up. In particular, they kept trying to repeal the law that halved our fuel consumption, in favour of a completely useless trickle of construction materials when you are literally freezing to death and voting away the heat, you idiots.

One faction smugly went outside during a whiteout against my orders, in order to bring back food when we already had three times what we needed. When the time finally came to decide whose grand plan I’d enact, the other faction complained that it was getting them killed, and started sabotaging the buildings that prevented the exact deaths they were protesting.

This was long after the first political protest by the Stalwart faction, which I left alone, figuring it best to let them march and occupy things, then throw them some concessions. They murdered 500 people. Then another 500. This went on until I sent in some guards, and the thirty deaths resulting from this, the game told me, had “radicalised” the Stalwarts. Somehow the word on the street was the people who massacred a tenth of the population because I refused to research “Thought-Correction Prisons” were normal, sound dudes, and I was a tyrannical dick for stopping them. What did I enact a propaganda network for?

The problem is that in shifting from survival to realpolitik, Frostpunk 2 becomes a management game about leadership, but it doesn’t give you enough means to actually lead. It’s telling that as soon as the game unlocked the ability to simply round up both radical factions – the Stalwarts were responsible for 85% of our deaths, but the others were trying to turn all women into breeding slaves, children into soldiers, and doing eugenics on the “weak” – I did it immediately and won the game. Oh sure, one of the survivors might try to assassinate me, but that’s only because the game forced me to put them into isolated “enclave” districts instead of shooting them all, who combined were now 1% of the population. I could have maybe won via the peace accord option, or by building them their own independent colony, but: a) fuck these psychopaths and b) those sounded like such a chore.

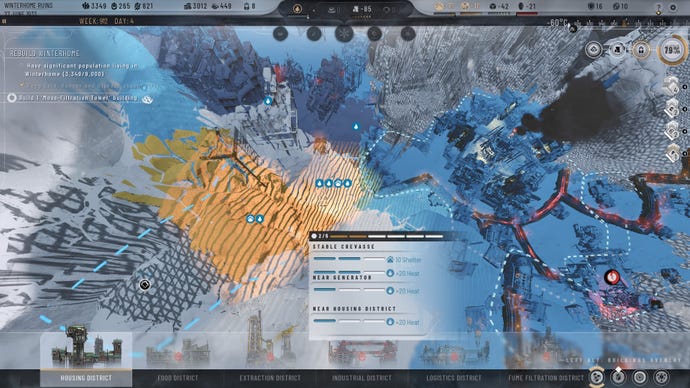

All the while you’re wrangling factions, see, you’re also building (visually similar) districts around the city to gather resources, ideally around bonus-applying hubs, with expansion buildings attached to customise districts to a rather complicated degree. Maybe you’ll convert materials into coal, and that into oil. The factories could recycle some material, the housing could have a guard post, hospital, or prison, the logistics district an expansion that helps its explorers work faster on the map. Many of these enable special actions that might trigger an event, and don’t forget they all might please a faction and nudge the zeitgeist somewhere. Oh and your eastern colony is out of food and the other one’s stockpile is full, and the council voted without you. No, we didn’t tell you this or reassign those workers for you. We were too busy pausing the game with indistinguishable audio alerts (but still making you scroll around the map to find its source), and pop-up messages that disappear if you press the spacebar that’s also pause.

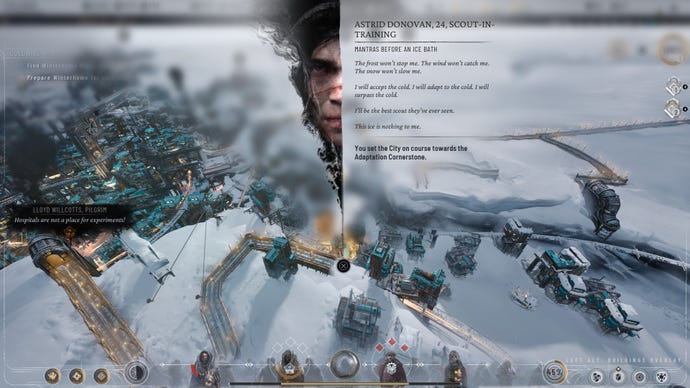

You build colonies, too. Many locations provide resources or immigrants, subplots with multiple resolutions, and occasionally a colony site, which you build from scratch like the city, then keep on top of balancing exports and stockpiles and potentially ongoing events. Its world map suffers the same fate as post-Frostpunk survival builders like Endzone and New Cycle; parts take focus away from the settlement, and other parts are a reductive, forgettable chore. And all the while, you’re getting interruptions. Some legislation had consequences, will you amend it? A man has some (great) flavour text. The problem you already solved is still solved. The nomads are grateful you sacrificed lots of oil and now they want a large supply of oil that you don’t have because you gave it up oh my god fuck off.

It’s very cool that there’s so much detail that specific combinations of laws can cause unique problems. It means the mere possibility of unintended consequences makes you wary of things that seem mechanically useful. But it is all far, far too much. I was crying out for someone to delegate to within two chapters, and though I’m curious to see alternative endings and events, the process of building and finding resources and manually adjusting every single district when population drops is too exhausting a prospect for a society I have little reason to care about without the motivating threat of annihilation. All that’s left is expanding for its own sake. I don’t think anybody has a sustainable plan here, and there’s nobody to like.

I want to love Frostpunk 2, and I think that’s precisely why so much of this review is negative. It deserves recognition for the courage to push into something new rather than play it safe. It’s far more compelling, interesting, and super atmospheric than its peers, but that ambition has cost it a singular intensity and focus that leaves its fresh narrative and design too contradictory to carry it to the same heights.

This review is based on a review build of the game provided by the publisher.