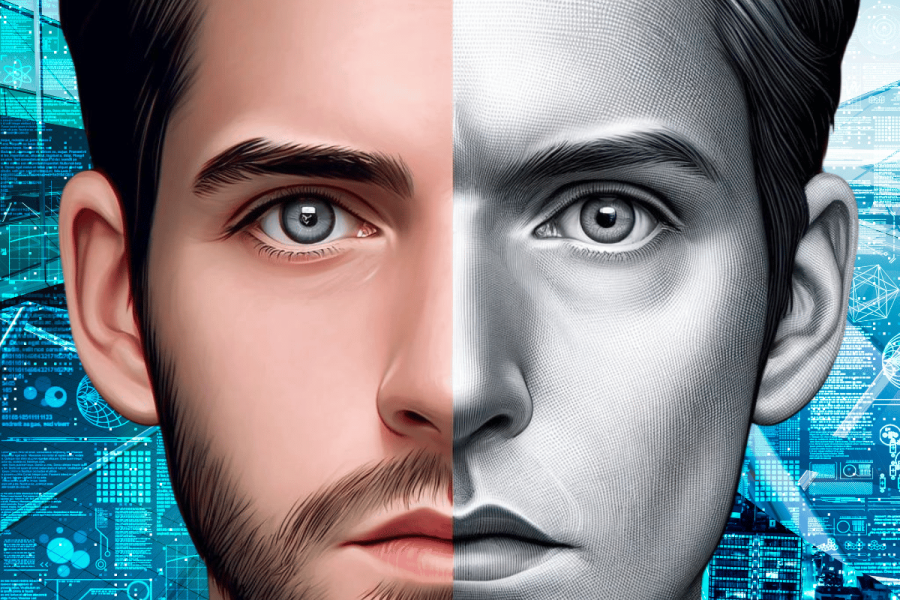

We live in a world where anything seems possible with artificial intelligence. While there are significant benefits to AI in certain industries, such as healthcare, a darker side has also emerged. It has increased the risk of bad actors mounting new types of cyber-attacks, as well as manipulating audio and video for fraud and virtual kidnapping. Among these malicious acts, are deepfakes, which have become increasingly prevalent with this new technology.

What are deepfakes?

Deepfakes use AI and machine learning (AI/ML) technologies to produce convincing and realistic videos, images, audio, and text showcasing events that never occurred. At times, people have used it innocently, such as when the Malaria Must Die campaign created a video featuring legendary soccer player David Beckham appearing to speak in nine different languages to launch a petition to end malaria.

Target 3.3 of #Goal3 is to end malaria once and for all. Join David Beckham in speaking up to end humankind’s oldest and deadliest enemy: #MalariaMustDie pic.twitter.com/Zv8hpXDCqy

— The Global Goals (@TheGlobalGoals) April 9, 2019

However, given people’s natural inclination to believe what they see, deepfakes do not need to be particularly sophisticated or convincing to effectively spread misinformation or disinformation.

According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the spectrum of concerns surrounding ‘synthetic media’ ranged from “an urgent threat” to “don’t panic, just be prepared.”

The term “deepfakes” originates from how the technology behind this form of manipulated media, or “fakes,” relies on deep learning methods. Deep learning is a branch of machine learning, which in turn is a part of artificial intelligence. Machine learning models use training data to learn how to perform specific tasks, improving as the training data becomes more comprehensive and robust. Deep learning models, however, go a step further by automatically identifying the data’s features that facilitate its classification or analysis, training at a more profound, or “deeper,” level.

The data can include images and videos of anything, as well as audio and text. AI-generated text represents another form of deepfake that poses an increasing problem. While researchers have pinpointed several vulnerabilities in deepfakes involving images, videos, and audio that help in their detection, identifying deepfake text proves to be more difficult.

How do deepfakes work?

Some of the earliest forms of deepfakes were seen in 2017 when the face of Hollywood star Gal Gadot was superimposed onto a pornographic video. Motherboard reported at the time that it was allegedly the work of one person—a Redditor who goes by the name ‘deepfakes.’

The anonymous Reddit user told the online magazine that the software relies on multiple open-source libraries, such as Keras with a TensorFlow backend. To compile the celebrities’ faces, the source mentioned using Google image search, stock photos, and YouTube videos. Deep learning involves networks of interconnected nodes that autonomously perform computations on input data. After sufficient ‘training,’ these nodes then organize themselves to accomplish specific tasks, like convincingly manipulating videos in real-time.

These days, AI is being used to replace one person’s face with another’s on a different body. To achieve this, the process might use Encoder or Deep Neural Network (DNN) technologies. Essentially, to learn how to swap faces, the system uses an autoencoder that processes and maps images of two different people (Person A and Person B) into a shared, compressed data representation using the same settings.

After training the three networks, to replace Person A’s face with Person B’s, each frame of Person A’s video or image is processed by a shared encoder network and then reconstructed using Person B’s decoder network.

Now, apps such as FaceShifter, FaceSwap, DeepFace Lab, Reface, and TikTok make it easy for users to swap faces. Snapchat and TikTok, in particular, have made it simpler and less demanding in terms of computing power and technical knowledge for users to create various real-time manipulations.

A recent study by Photutorial states that there are 136 billion images on Google Images and that by 2030, there will be 382 billion images on the search engine. This means that there are more opportunities than ever for criminals to steal someone’s likeness.

Are deepfakes illegal?

With that being said, unfortunately, there have been a swathe of sexually explicit images of celebrities. From Scarlett Johannson to Taylor Swift, more and more people are being targeted. In January 2024, deepfake pictures of Swift were reportedly viewed millions of times on X before they were pulled down.

Woodrow Hartzog, a professor at Boston University School of Law specializing in privacy and technology law, stated: “This is just the highest profile instance of something that has been victimizing many people, mostly women, for quite some time now.”

#BULawProf @hartzog explains, “This is just the highest profile instance of something that has been victimizing many people, mostly women, for quite some time now.” ➡️

— Boston University School of Law (@BU_Law) February 1, 2024

Speaking to Billboard, Hartzog said it was a “toxic cocktail”, adding: “It’s an existing problem, mixed with these new generative AI tools and a broader backslide in industry commitments to trust and safety.”

In the U.K., starting from January 31, 2024, the Online Safety Act has made it illegal to share AI-generated intimate images without consent. The Act also introduces further regulations against sharing and threatening to share intimate images without consent.

However, in the U.S., there are currently no federal laws that prohibit the sharing or creation of deepfake images, but there is a growing push for changes to federal law. Earlier this year, when the UK Online Safety Act was being amended, representatives proposed the No Artificial Intelligence Fake Replicas And Unauthorized Duplications (No AI FRAUD) Act.

The bill introduces a federal framework to safeguard individuals from AI-generated fakes and forgeries, criminalizing the creation of a ‘digital depiction’ of anyone, whether alive or deceased, without consent. This prohibition extends to unauthorized use of both their likeness and voice.

The threat of deepfakes is so serious that Kent Walker, Google’s president for global affairs, said earlier this year: “We have learned a lot over the last decade and we take the risk of misinformation or disinformation very seriously.

“For the elections that we have seen around the world, we have established 24/7 war rooms to identify potential misinformation.”

Featured image: DALL-E / Canva