OPINION: The saying “it’s not what you got, it’s how you use it” could be interpreted in many ways, but for the purpose of this Sound & Vision column, I’m going to use it in reference to TVs, and not whatever you might be thinking of...

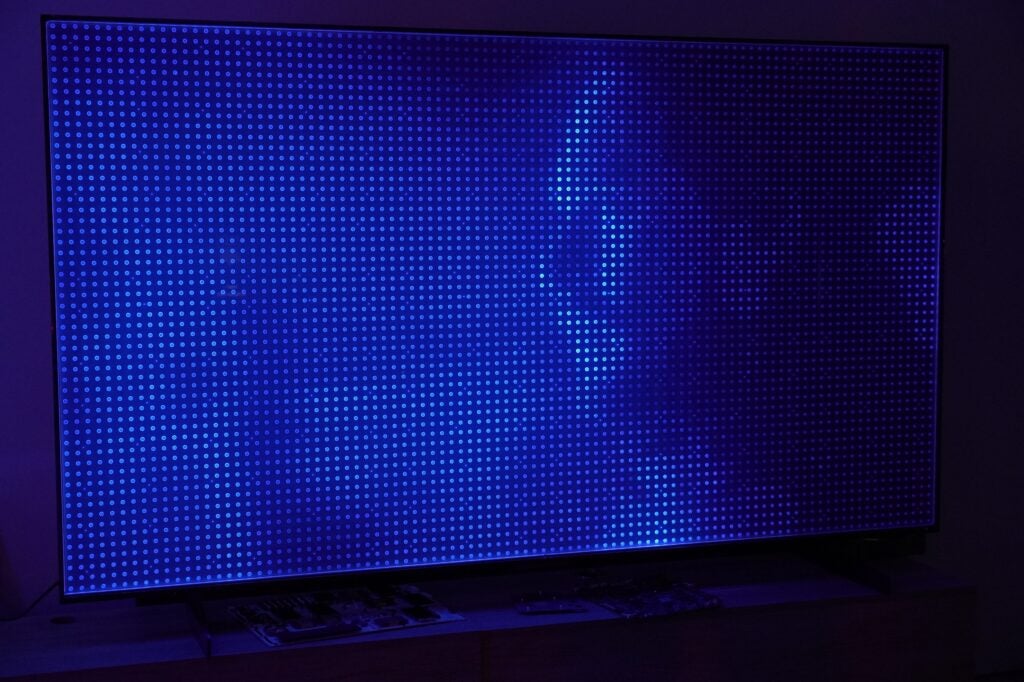

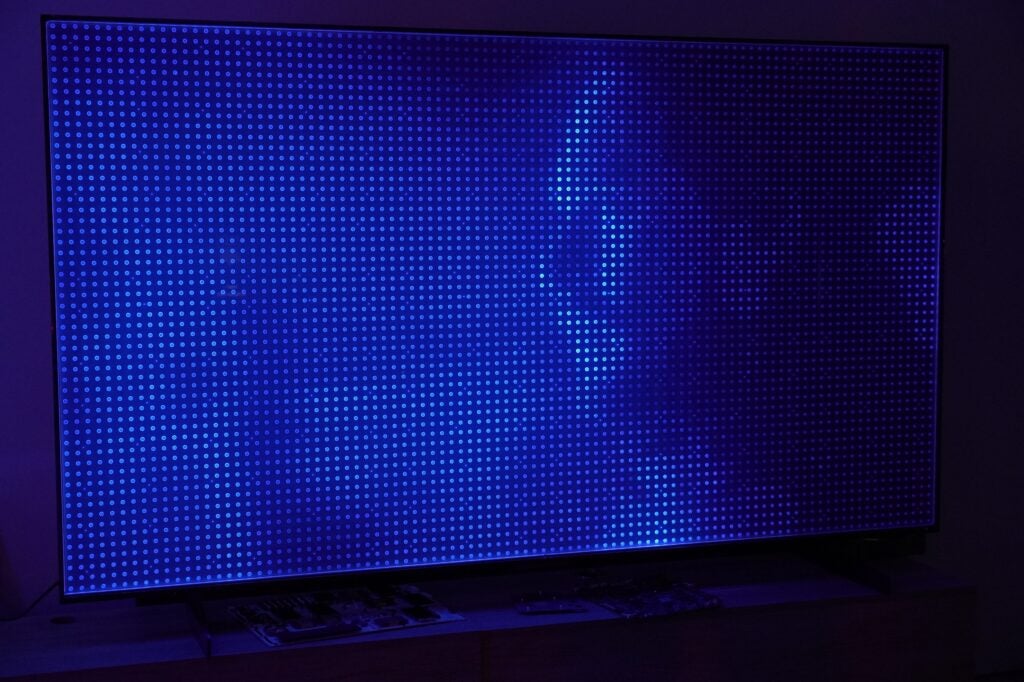

This week saw the announcement of the X11H Mini-LED TV from TCL, a name that sounds like it should be a SpaceX rocket. It has a panel capable of 6500 nits of brightness with over 14,000 dimming zones.

In recent years, the TV industry has had a thirst for ever-greater brightness, and TCL is no stranger to increasing the light output of its TVs (or trying to manufacture one as big as they possibly can). It has the feel of an F1 car in pre-season testing, going for a glory run to get their name in the headlines. I’m writing about it and you’re reading this article, so it must be working.

But to go back to “it’s not what you got, it’s how you use it”, in my experience, it’s something of a fallacy to equate bigger numbers with better performance, especially when talking about dimming zones.

The high number in the X11H will focus debate on how technological advanced it is (which is surely the outcome TCL wants), and about how the TV is so bright it’ll be like the scene in Danny Boyle’s Sunshine when Cliff Curtis’ Seale takes off his glasses. Perhaps apply some factor 45 sunscreen and a welder’s mask before you watch any bright content.

But there is more to backlight control, pinpoint blacks and high brightness than having a huge number of dimming zones. It’s more important as to how those dimming zones are controlled, and what they’re instructed to do.

I’ve reviewed TVs with high dimming zones and still seen blooming and clouding. I’ve seen TVs with far fewer zones and not seen much, if at all.

I can see why companies such as Sony are reluctant to get into the numbers game, as it creates the perception of more is better and less is not as good. I’ll reference the upcoming and (so far) secretive Sony TV coming later this year, which I’ll designate as the ‘Triple M’ – the Mystery Mini-LED Model.

It features Sony’s proprietary technology, fitted inside tiny 22-bit LED drivers capable of a huge amount of processing that can more precisely tell and control what the Mini-LEDs are doing.

Compared to a rival model, which my assumption had more dimming zones, the Sony prototype was better not just in terms of backlight control with its black levels and more precise light output, but the gradation of colours (the transition from one shade to another).

Rather than make the story about the number dimming zones, it’s about the algorithms and processing deployed that tell Min-LEDs how to interpret and respond to the picture information they’re receiving. Don’t go down the road of more dimming zones, it’s a cul-de-sac. It’s about the quality of the processing.

Another aspect that’s gaining traction is that high peak brightness is the direction that TVs are travelling down (or up, I should say). That has its advantages: higher brightness copes better with reflections and ambient light, as well as delivering on more of the potential that HDR brings to table with improved colour volume.

Though OLED is earning prime time in front of customers, Mini-LED represents its biggest threat. OLED has perfect blacks and infinity contrast, but it can’t match the brightness of Mini LED in every test case or at every price point. There is no such thing as a perfect TV, but in the chase for higher brightness that some TV brands believe in, Mini-LED is the screen of choice.

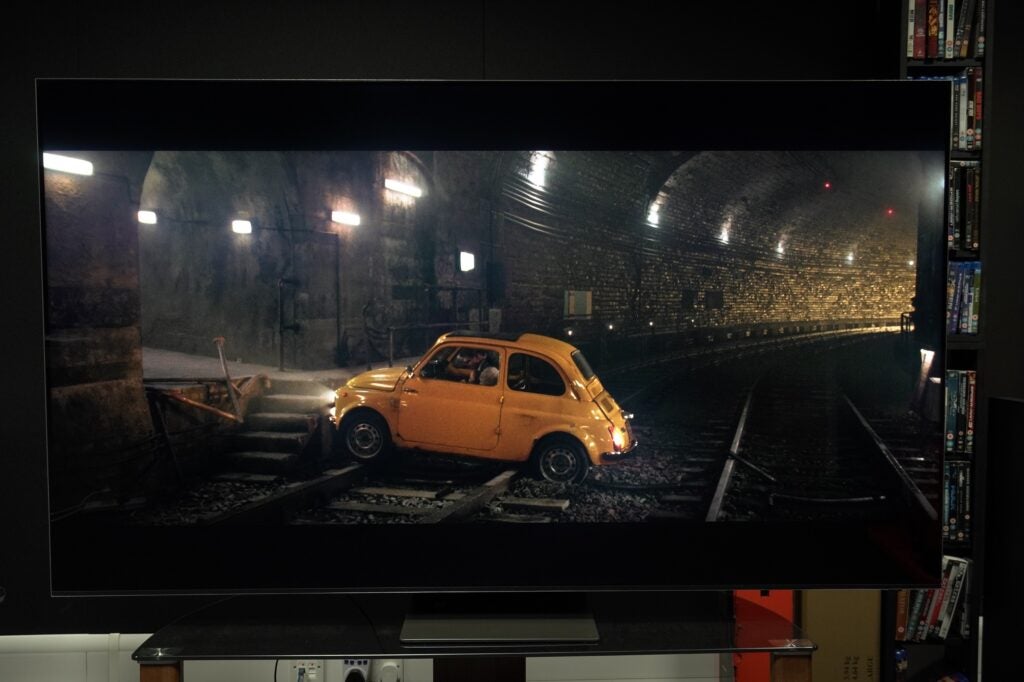

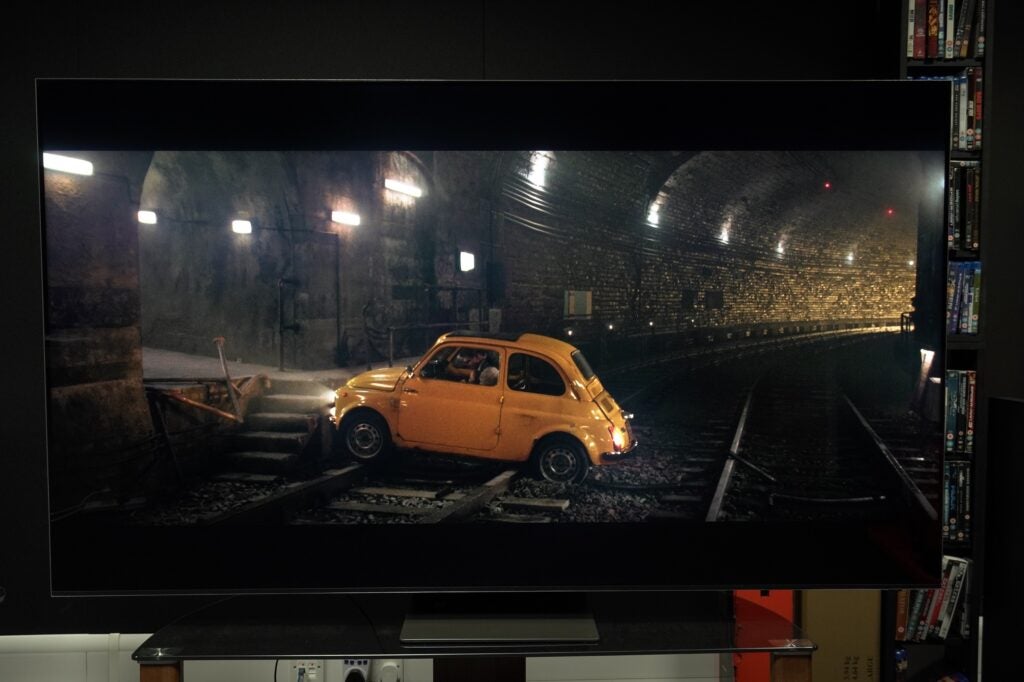

But other manufacturers would refute this. If you look at the direction Hollywood mastering suites are going in, the action isn’t happening at the top end, but taking place towards the darker end of the brightness spectrum.

Filmmakers and mastering specialists are much more interested in darkness – you only have to look at the infamous Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon episodes, the latter clocking in at a miserly 1 nit. It’s great having a peak output of 6500 nits, but that’s 6499 more than that scene will ever require.

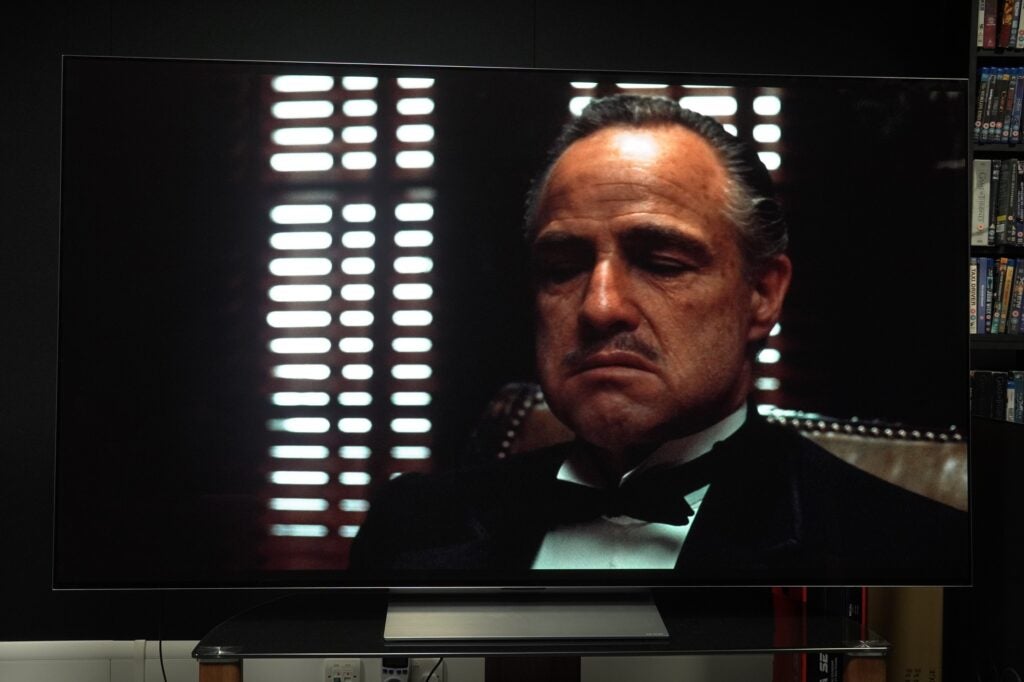

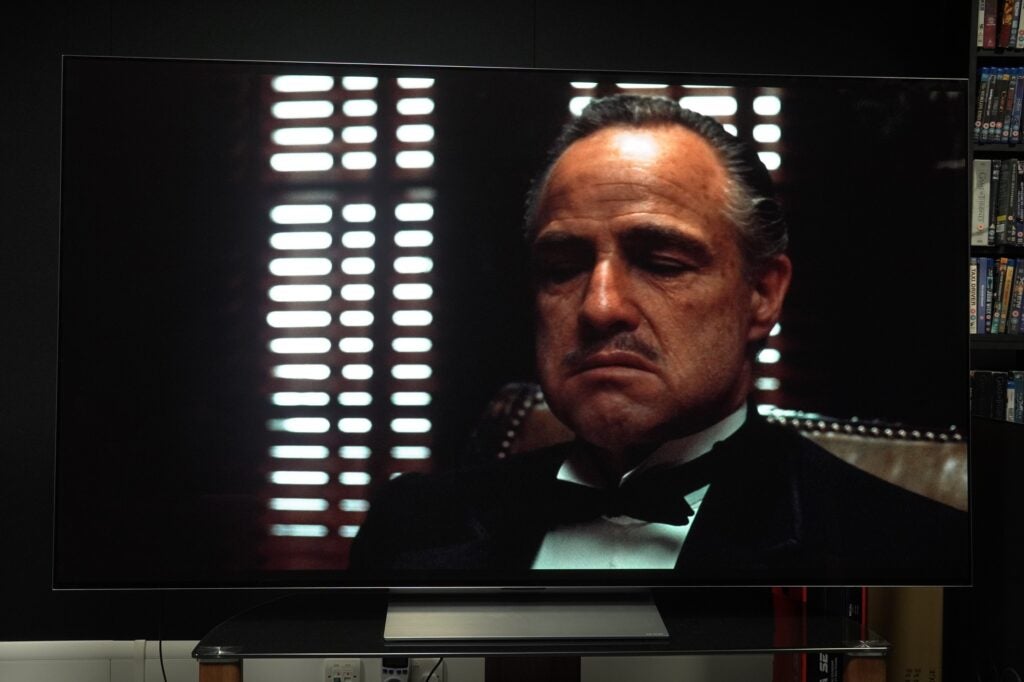

Look back to the past and the likes of legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis, and the films he lensed such as The Godfather, and how he dispensed with the saturated brightness of studio films to work in the shadows, earning the nickname the Prince of Darkness.

TV manufacturers will try to find new ways to push the technology at their disposal, though I’m sceptical about whether the high brightness future some are imagining is going to happen, at least any time soon. Don’t get tricked by the high numbers – few films are even mastered beyond 4000 nits.

Even if we’re talking about future-proofing TV sets, it’d be years (perhaps a decade) for content that bright to be regularly available. You only have to look at 8K to see where promise led to disappointment.

It’s not what you got, it’s how you use it; and the TVs with this motto in mind will be the ones you should really be keeping an eye out for.